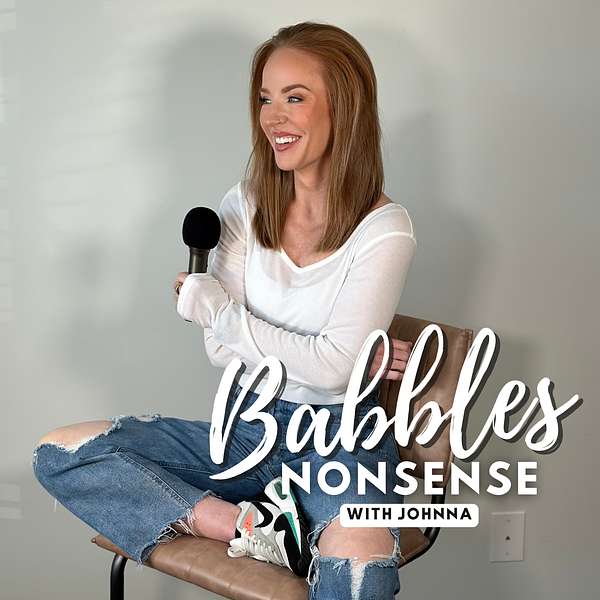

Babbles Nonsense

Welcome to my verbal diary where I want to discuss any and all things that is essentially on my mind or have wondered about. Sometimes I will be solo and then other times I will have some amazing guests to bring all different perspectives in life. The ultimate goal is to hopefully bring some joy, laughter, inspiration, education, and just maybe a little bit of entertainment. Don't forget to like, rate, and share the podcast with a friend!

Babbles Nonsense

Navigating Autism: A Mother's Journey of Advocacy, Insight, and Hope w/ Tracy

#150: What if understanding autism could completely change the way you perceive the world? Join us for a heartfelt conversation with Tracy, a passionate advocate and mother of an autistic child, as she shares her personal journey. From identifying her son David's early developmental challenges, such as delayed speech, to the emotional rollercoaster of receiving an autism diagnosis, Tracy's story offers invaluable insights. Through her experiences, we explore the essential role of parental intuition and the often-overlooked complexities of navigating autism therapy options amidst overwhelming information and long waitlists.

Discover the misconceptions surrounding autism that many still hold today. Tracy dispels myths about its causes, emphasizing the individuality and diverse abilities of those on the autism spectrum. As she recounts the journey of distinguishing between potential seizures and unique expressions of autism, Tracy sheds light on the critical need for better resources and school advocacy. Her candid reflections underscore the societal and educational changes necessary to support children with autism and their families effectively.

Tracy's story is one of resilience and hope, as she dreams of a fulfilling future for David. From his progress in speech and occupational therapy to the challenges of transitioning between tasks, this episode is a testament to the triumphs and struggles of parenting a child with autism. We also touch on the broader issue of mental health stigma and the urgent need for societal understanding. Tune in to celebrate David's achievements and Tracy's unwavering dedication, while gaining a deeper appreciation for the beauty of neurodiversity.

Find Tracy here: https://www.instagram.com/t_raynorsaurus_rex/

You can now send us a text to ask a question or review the show. We would love to hear from you!

PodMatchPodMatch Automatically Matches Ideal Podcast Guests and Hosts For Interviews

Follow me on social: https://www.instagram.com/babbles_nonsense/

What is up everyone? Welcome back to another episode of the Babbles Nonsense podcast. On today's episode, we are talking about autism, but we're talking about it from a parenting perspective versus a medical or therapy perspective. My good friend, tracy, was so gracious and allowed me to interview her on this topic. She is a mother of an autistic child and she loves spreading awareness about autism. And before we get started, I wanted to put a caveat out there that this is Tracy's personal journey on her parenting and what she had to learn and overcome on her own journey. So just keep that in mind while listening. We all know that parenting is a sensitive subject and everyone does everything differently. There's no right or wrong. There's no one telling anyone what they should or shouldn't do, so just keep that in mind. All right, guys, here we go.

Speaker 1:I have my friend Tracy back today. Y'all all may know her from the laser tattoo removal episode that everyone seemed to love. So welcome back, tracy. Thank you, it's good to be back. So I wanted Tracy to come on today because we talk a lot, we're friends and she has a child with autism and I just wanted to talk about that because I don't feel like it's talked about enough and I wanted to get it from a perspective of obviously not like a child psychologist, but coming from just someone who has lived it. So I wanted her perspective and she so graciously said that she would come on and talk about this. So this is just going to be a conversation, guys. It's not to, you know, be like medically correct or anything like that, it's just Tracy's experience. So it's from her point of view, all right. So, yeah, let's just dive on in. So, tracy, kind of talk to us about, like your experience so far with David, your child who has autism, like just kind of a brief expert or excerpt, and then we're just going to dive on into it.

Speaker 2:Okay, well, I think the first thing is like people ask is well, how did you know what you know? What were things that prompted you to think to get him tested? And for me, you know, most kids, by the time they're a year old, they're saying mama, dada. I mean, they're saying you know little words. And David wasn't.

Speaker 2:He wasn't saying anything and I talked to his pediatrician and the pediatrician and of course everybody around me is like he's the youngest, he'll talk when he's going to. You know, babies tend to talk later because their older siblings talk for them. And so I kind of just said okay, and I kind of pushed it aside. And then at 18 months old, he still wasn't talking. And so I go back to his pediatrician and and then you know the pediatrician's like well, he's probably just got a speech delay, let's start him in speech therapy and that that was it. No, no worries, because physically he was progressing as normal, like hitting every milestone. So it was just the speech, just the speech at first. I mean, that's the only thing that I'm looking back.

Speaker 1:I can see other things, but yes, that was my only concern and we'll touch on that Like once you talk about kind of like what you noticed at first, and then I want us to go back and talk about like after you kind of know more about it right and looking back what you then saw and recognize, so that other people may like, if they're experiencing something, maybe they would recognize sooner than a physician or something like that right and, like I said, you know I have four older children.

Speaker 2:So really the speech, because physically the milestones were on point, so the speech was the only thing I noticed. So the pediatricians like let's get a in-home speech therapist. We had an in-home speech therapist for an entire year who would come weekly and meet with David and in that entire year he gained nothing, not one word, no improvement whatsoever. And at that point so let's say see he was eight, so he's two and a half by now.

Speaker 2:So at two and a half years old, kids are talking they're having a few words, small sentences, and he had nothing so I could. And then, but during that time I'm thinking something else has to be going on, like this is more than just being the baby not talking. So that's when I started paying closer attention. I'm noticing he's not answering to his name, he's not making eye contact, he's not talking. You know, I mean just all these little things.

Speaker 2:So I go back to the pediatrician and I'm like listen, if you tell me that I'm crazy or that you know not to worry, I trust you because I've been with him forever. But I said, here's everything that I noticed about David. And I went through all the list of he's not speaking, he doesn't make eye contact, he's not paying attention. You know he has these, even even to the point of he's having these. He zones out a lot Like he's just, you know, not looking at you and and I went through all these things and the pediatrician, when I got done, listing all the things that I had noticed, he goes that sounds like autism to a T. I want you to have him evaluated.

Speaker 1:And you said he was two and a half when you so that was when he was two and a half when you told the physician this.

Speaker 2:Yes, he was about two, and a half, yeah, cause I think he was about eight, about between 15 and 18 months, when we started the speech therapy, so it was a year from that, so he was right under two and a half years old when I called and got him set up. And it takes forever and that's something. It takes probably six to eight months to get in to have your child tested. It is an extremely long wait list.

Speaker 1:I didn't realize that that's the frustrating part, because I don't know why I don't, and that's one of the questions that I was going to ask is like how young can a child be tested?

Speaker 2:Usually it's. I want to say three, which you know luckily we were. By the time we got there he was a little over three, so I could be wrong on that. It might be two and a half. But I want to say three is the youngest. They'll test them, so time-wise we kind of fell where we needed to, but it's frustrating to have to wait.

Speaker 2:Um, but it's an intensive thing where they, you know, they go in and you're there for a few hours and they're observing like behind a two or one way mirror and then they come in and observe, and they do all these things.

Speaker 1:I was wondering how the testing went Like if they came in and was trying to ask him questions, cause he's three like they do, it's not like a. It's not like an adult where they can like understand what you're doing.

Speaker 2:But I guess, based on his behaviors, Right and I mean, like I said, it's not just a oh. They come in and they see you for 30 minutes. They're like, yep, see you for 30 minutes. They're like, yep, he's autistic. I mean they base it on like you're filling out these questionnaires, they're asking you these in-depth questions of what you notice and then they're getting you know their diagnosis. They're watching him, like I said, part of the time they're watching him through a one-way mirror just to see how he interacts with me. Then they come in and they're asking him to do certain tasks and then they're evaluating him. You know over the course of several hours how he plays, how he responds. And then they you know there's the trying to think like a. They have their criteria, their list of things that he either does like a normal three-year-old's going to do, or he doesn't.

Speaker 2:And before I even left the office she stopped me. The doctor said hey, I've still got to write, or he doesn't. And before I even left the office, she stopped me. The doctor said hey, I've still got to write up my formal report. But he's most definitely autistic. I've even heard that from a pediatric neurologist because we thought he was having seizures. Apparently, autistic children are great at zoning out and I didn't know that David would be in the middle of like running, like he'd be out in the backyard, backyard he'd be running and he would stop dead and just stare into space and not respond.

Speaker 1:I mean, that sounds like a focal seizure. Yeah, it does, it does.

Speaker 2:We observed it so many times, like he'd be in the middle of just doing something, just stop and stare and you could not wave your hand in front of his face, you couldn't talk to him and I took him to two different places. I took him one locally, had a um in Huntsville to do um an EEG, and they were like we didn't catch anything.

Speaker 2:But then again, you know, if you don't catch anything while you're doing it and I was like I need a second opinion, like this is worrying me. So we went to Vanderbilt and met with a pediatric neurologist at Vanderbilt and he gave me the best advice. He said if you and it was funny to me he goes stick your finger in his ear. And I said what? And he goes. You can't pull a child out of a seizure, he said. But you can distract a child, he said.

Speaker 1:So if you stick your finger in his ear, they'll distract him. He goes that's not a seizure, and so I was like, well, I wish somebody had told me that like a lot of money ago.

Speaker 2:So was the pediatric neurologist before he was tested or after it was after, no, it was before, it was because we were waiting to come up. I remember that because I told him. I said we have the suspicion he may be autistic. We're you know, we're waiting to be diagnosed. And even before then, because I remember he looked at me and he said he is most definitely autistic.

Speaker 1:Cause I was about to ask if a neurologist didn't tell you cause obviously they study the brain. I was going to be like questioning, like wow, this really is hard to diagnose.

Speaker 2:He looked at me cause I was like really, he goes, he's most definitely autistic and I said okay, and that was because I remember thinking I don't even have the diagnosis and I have a pediatric neurologist at Vanderbilt going yep, nope, he presents as autistic and he said autistic children are great at zoning out.

Speaker 1:So did you ever stick your finger in his ear? I?

Speaker 2:have. Does it distract him? It does Cause he, you know, he does his little shoulder up like stop touching me thing you know so but I'm like that's a great thing If parents are like are they having a seizure Right? Especially if your kids because that was right before we had him diagnosed and that's a scary thing to think. Your kids just staring into space, space you know, and not moving and not responding right and he said you could do that to a child actually having a seizure and it's they're not going to move.

Speaker 1:They're not. They're not going to come out of it. And that's the one thing, like when I worked in the er, even with adults, like you could tell when someone was faking a seizure, like there was ways to tell right because some people could fake very well, right, but there was ways you could tell that they were faking and like sometimes they would have a diagnosis of pseudo seizures, which means fake seizures and you're just like well, either you do or you don't right?

Speaker 2:so okay, well, I mean in. Well, it went beyond that. Like what was a little scarier for me is david we would. It would be around nap time again before he was diagnosed. It was before we even saw the neurolog. Is David we would? It would be around nap time Again before he was diagnosed. It was before we even saw the neurologist or anything we would. He would be laying there, no TV on, no distractions or anything. We're just laying in a room, quiet, dark, taking a nap, and he would start laughing at nothing. That would scare me. It was a little creepy, you know too. But also you're thinking okay, are you saying something?

Speaker 1:So it's like, what is he thinking in his brain to be laughing like that?

Speaker 2:Well then, you know, of course, I start reading. I'm like he's zoning out, he's staring, he's laughing and that's all symptoms of seizures. And so then I'm like really freaked out, thinking he's definitely having seizures. But apparently he just thought something was funny, which is a relief. Now it's more creepy to know that.

Speaker 1:Does he?

Speaker 2:still do that? He doesn't. He did when he was little. He'd be in the car sometimes and he'd be looking out the window and he would just be dying laughing. We'd be laying down to go to a nap. I just attributed it to his uncle Past literally two weeks before he was born.

Speaker 1:I'm like hopefully that's his uncle talking to him or something. So you've gotten your diagnosis at three years old. Yes, and how did they go about telling you? What did they tell you like to look for, to do? Like what were the steps after being diagnosed? See you?

Speaker 2:think there would be all these here's what you do.

Speaker 1:Here's a step by step.

Speaker 2:Here's a pamphlet here. The overwhelming part them telling me he's autistic was a relief because I kept saying there is something wrong. Like I have raised four other children, I've never seen anything like this, like something's different. And to be told, yes, he is. I was like, okay, I'm not crazy, I know my child, it was, you know, you know, just okay. Now what do we do? This is the sad part. They give you a ton of resources which is great, don't get me wrong but they're just like here, you go Bye. They don't tell you you know, these are the steps you need to take, these, um, this is what works best. I mean, nothing is literally just here's all the resources we have in this folder. Figure out what you're going to do with your kid and they just send you off. And if you don't want to do anything with your kid, you don't have to, which is your choice. But I'm like I don't know, like there's so many different therapies.

Speaker 1:So they don't sit you down and say like they don't, like I don't know. I feel like the process which I know, like you said, they're very clearly they're booked out six to eight months. So, they don't have that kind of time, which is sad, and maybe that's something that we need to publicize and try to work on. But you would think they would sit you down or maybe send the parents to a therapy session or counseling session and say here are some steps.

Speaker 1:Let me explain each one to you thoroughly so that you can decide what's best for you and your child, Because we also have to think about cost, right? Which we're going to get into, because I printed off some facts that were even kind of astonishing to me, right, but like we have to get into cost, because people with autism need different things.

Speaker 2:Yep Different resources, right yeah.

Speaker 1:So you have this packet of papers Yep Sent home. How do you decide, like do you go home and do your own research? How do you then go about deciding like what's best for you and your family?

Speaker 2:So what I did as I went home and, of course, when you have all this new information, I literally went home and read every single thing in that packet. I called every single number that they gave me. I mean, I was just like give me every resource. And then you get an even lonelier, sadder. You go down that road because here's the thing you start calling these places going oh okay, well, they're suggesting this therapy and this therapy. And you call and they're like we're on a wait list. We're on a wait list. We're on a wait list or we're not accepting new patients.

Speaker 1:My aunt calls that analysis, paralysis, when you're giving too much information.

Speaker 2:It was.

Speaker 1:That you just stop, because it's like this is too much.

Speaker 2:It was a lot, it was a lot of information. So all I knew to do was just look at everything, read everything I could find and call every number that they gave me, every resource, every therapy, and I did, and there's so many wait lists I just kind of I did, I sat and stopped for a while. I mean, I stopped for a couple months. I'm like, okay, there's a long wait list on literally everything I'm trying to get into. Let me just sit and do my own research. Let me just take a step back, read everything I can and figure out what's good, what you know in. One of the things that was suggested was ABA therapy and, of course, what does that stand for?

Speaker 2:That's what I was about to say. It is my mind just went blank. But it's like a behavioral therapy. It's basically where they're trying to help your child fit into society like normal. And don't get me wrong, I've met, I know personally people who've had their children in ABA therapy and they love it. It worked perfect for their child and it was a good thing. And I've known other people that wouldn't touch it with a 10 foot pole. They're like it's, it's a horrible it was. It was just they felt like it was almost abusive. So you're going to have. I've found through my research and, like I said, this is personal Um, it's a black and white. You either love it or you hate it, and I've not found any in between.

Speaker 1:Well, I mean, it's kind of almost like therapy, right? Like a lot of people either love therapy or they hate it, based on their therapist, based on the experience they had with that certain particular person so it's probably whoever's running the group, whether they're doing an amazing job and giving them wonderful support. And I'm not saying like people who are doing it but I'm saying it's a form of therapy it is.

Speaker 1:I've been to multiple therapists and there's some therapists that I'm like this is doing nothing for me, so why am I wasting my money? And then I've been to some some therapists that I'm like this is doing nothing for me, so why am I wasting my money? And then I've been to some therapists where I'm like this was life changing Right.

Speaker 2:I agree with that to a point and I'm on the side. I can't say that I hate it because I didn't do it, but I'll tell you why I chose not to. So, yes, I think you can absolutely have wonderful and I think that's why people loved it. The people who did love it is because they had a great therapist.

Speaker 2:Yeah, and they did things that actually helped their child. The reason I chose not to do it One it's extensive. When they ask you to do ABA therapy, they're asking you to go up to like maybe 40 hours a week, five days a week.

Speaker 1:This is a full time job. It's a three year old and it's a three-year-old and it's.

Speaker 2:It's a long time to be away from your family and I'm just like that's not my thing. I don't agree with that to how it's.

Speaker 1:So, yeah, go ahead. You work 40 hours a week, right? So how are you supposed to then add 40 hours a week? That's an 80 hour work week for you, not saying that you don't love your child or that you don't care for your child, but how is a working mom supposed to add on 40 extra additional hours when not only do you just work 40 hours at your job, you then come home to be a mother to your four other children, cook clean, be a wife all those things.

Speaker 2:And that's the thing they're supposed to go during the day. And don't get me wrong. People are going to say, oh well, it doesn't have to be 40 hours, and they're right, it doesn't. They can adjust that. Some people do 20 hours a week. There's people who do less than that, but still again, but the suggested is from and this is, like I said, from what was suggested for me. So I don't want people to come at me saying, well, I do this and it was only this and that's great, that's what was suggested for you, but I didn't want to do that One because it took a ton of time away. I just feel like that's a long day for kids, it's a long day for me at work.

Speaker 2:Can you imagine a three-year-old having to deal with that? Well, their attention span's. Not that An autistic kid has no attention span, but to me it was more. I want you to conform to what quote unquote a normal child does.

Speaker 1:And here's the thing.

Speaker 2:I wouldn't change David. That's my son with autism. I wouldn't change him for anything If he doesn't want to make eye contact with you ever in his life, I don't care. That is not my priority. It is not at all.

Speaker 1:No, I get you Like. I try anytime I like interview someone or have a conversation. I try to find relations in my life and like someone or have a conversation. I try to find relations in my life and like. I find that a lot like when because my personality is not very, you know, the best for everyone, let's just put it that way. And I used to try so hard to change my personality to fit in with everyone else and then it got to the point, you know, through therapy, that I was like why am I doing this? No one else is changing their selves for me, or no one else is trying to help welcome my personality into the world. So I get what you're saying. When it comes like why can't the rest of the world be conditioned to just accept everyone?

Speaker 2:Right, just let him be who he is. If he wants to go play by himself because David can be, he loves to play with kids but he's very much a loner he may just get up and go be by himself. And it's not sad. I know people are like, oh, he's off in the corner playing by himself. He wants to. He gets overwhelmed, overstimulated. That's his, that's his time and that's okay and it's like why should I send him to therapy 40 hours a week so he can learn to play with other kids when he that he doesn't want to? I don't always want to be around people you know so why should we have to do those things?

Speaker 2:If he doesn't want to, if it makes him uncomfortable to make eye contact, why is it so important to make him do that? It's like it's not that he's in, is not what's?

Speaker 1:not important to him, it's important to everybody else to make everybody else feel comfortable, right, and that's what it's important for and my goal as a parent is not to make everyone else feel comfortable.

Speaker 2:It's to make sure my child is happy and he's loved and he's productive and he grows up to do all the things that he can do.

Speaker 1:There's a show that I was telling you about on I think it's on Netflix and I cannot remember the name of it and I I meant to look it up before this podcast, but it's about an autistic child and I just I loved it. I wish they didn't discontinue it, because this kid literally tells everybody like he is so honest and he is like he just tells people what he's thinking at all times and I'm like, honestly, why can't the world be like that? Because then there would be no like. Do they like me? Do they not like me? Do they like my personality?

Speaker 2:There would be none of that. David is a very honest person. Like he says what he thinks. You know if you know.

Speaker 1:And you're like hey, david, do you like this shirt? No, mom.

Speaker 2:He would just tell you no, you know, it's like sometimes I want to sing in the car, and he's like mom, please be quiet. And I'm like Like okay, like he just and he's not being mean, that's just he's honest and he's he's never. But that's what I love about him he never tries to be hurtful. He's just super honest in what he wants and how he feels. And you know where you stand with David If he there's another show on Netflix.

Speaker 1:I just it popped into my head. Have you seen living with Beth? No, I haven't. So it's about Amy Schumer. I think it's like a based on her life. And she actually. I hope I'm not getting this wrong, don't quote me guys verbatim, but she actually married someone with autism.

Speaker 2:Yes, it is her.

Speaker 1:So she married someone with autism and like she recognized that he was not acting like the rest of the world. So they went and had him tested later in life and come to find out he has autism. But she says the same thing. She was like it's hard, but I love him so much. She was like he's so honest with me. If I'm, if I'm doing something crazy, he calls me on it.

Speaker 2:And, and I love that you know- what?

Speaker 1:maybe that's what I need in my life. Maybe we need more autism in the world?

Speaker 2:Maybe in the thing is, you know, I know people look at autism as a disability and I so do not, just because there's no guessing where you stand. You know they, like you said, very honest, very open, honest.

Speaker 1:And it is weird because it's when we think disability like coming from the medical perspective like we're thinking like wheelchair access, we're thinking yes, we're thinking what? Some other examples like you need crutches, you need a cane, you need, you need your vision impaired, you're hearing impaired. We think disability, like that. But then, when it comes to learning, impaired, right, autism, actually you're very smart.

Speaker 2:Oh, David is extremely smart.

Speaker 1:And it's almost like you're so smart that you can't fit in with a social norm because, quote, unquote, they're too dumb for you. Almost, that's almost what it's like.

Speaker 2:I feel like that with my five-year-old sometimes. I mean he knows things that I don't and I'm like that's not true and I'll look it up. Things that I don't and I'm like that's not true.

Speaker 1:And I'll look it up. I'm like, oh, it is true. Okay, Are you smarter than a fifth grader? No, or five year old? No, so so, going back a little bit, so you got him tested at three. They gave you the resources. You know, what did you end up choosing to do with him?

Speaker 2:So we started out with just doing occupational therapy and speech therapy. That's the two things we started doing at first. Speech therapy was huge. Now I started them out at one place, wasn't crazy about it, and that's okay to like you said, you find therapists you're crazy about and some you're like this isn't working for us. So we switched. We ended up with Huntsville Hospital Pediatric Audiology and Therapy and they are amazing. I saw a huge difference just the way they worked with him and he went from being nonverbal and when I say nonverbal, he had no functional language. He couldn't tell me if he was hurting, if he was hungry or thirsty.

Speaker 1:To me, that's the functional language when that was going on, did anyone at any point test his hearing to make sure he wasn't?

Speaker 2:deaf. Okay that I'm glad you brought that up, because, yes, at first I thought, well, maybe he's hearing impaired. Unfortunately for us, when David was just little I mean maybe less than a year and a half old, maybe a year and a half he had to have tubes put in his ears. So we did take him to an audiologist and they did hearing tests and when they're that little you can only do the only test you can do. Well, two things. One, he had tubes put in his ears and they do this thing where they blow air in the ears to test the pressure against your eardrums. But because he had tubes in his ears they couldn't do that. So they couldn't like properly test it.

Speaker 2:So they put us in a booth and I got to hold him and they're sitting outside the booth and they're whispering like words that'll either come from the left side or the right side, and if David looks in the direction they're talking like a big, giant toy lights up. The flaw in that is, you've got an 18 month old child who is constantly looking towards the toy that might light up. So we think he can hear because he did look. But then he got to where he's like oh, these things light up every so often, so he started looking around.

Speaker 2:He just starts looking around. So we knew he could hear in that and I knew he could because, like certain TV shows would come on that he liked and he would pay attention, he would zone into that.

Speaker 1:Okay.

Speaker 2:I didn't think he couldn't hear, it was just he wasn't going to pay attention to you. He's like I'm not looking at you, I've got better things to do and.

Speaker 1:David is the cutest, sweetest child.

Speaker 2:He is. He is the cutest, sweetest child.

Speaker 1:So now looking, so you go through occupational and speech therapy and now he's five. So how does that look from three to five with your therapy Like does it progress? Does it get less? How does that like? What do you see?

Speaker 2:changes in him. So the biggest change we saw since speech was our biggest concern at first and there's other things I'll talk about, but the speech was our first thing. The changes I've seen was he went from being nonverbal and I say nonverbal, he could name things. If you just pointed at something and said what's this, he could tell you what it was. And then he got to where he would put a couple of words together and that was huge for us. It wasn't often, but when he did we were like, oh my gosh, today he can make sentences and I know for a five-year-old, five-and-a-half-year-old that's normal for everybody else and not for David. He still doesn't talk a lot.

Speaker 1:No, he doesn't. I'll try to talk to him at church and he's like no. Yeah, he looks at you and he's like I don't know you girl.

Speaker 2:No, but every once in a while, and I'm like David, it's okay, I wouldn't talk to me either.

Speaker 2:He'll make a sentence or two, and the other day he put two sentences together and it just floored me. Every time he progresses it just floors me and I'm just like he's doing so. Well, you know, and you know other kids are just like talking your ear off and I'm just he's doing, I think he's doing great. He's made leaps and bounds in progress. The other things he was having issues with occupational therapy, things were like transitioning. He had really hard times transitioning between one task to another. He would get upset, have meltdowns, like if he was outside playing, there's nothing in the world that would make him want to come inside. And it didn't matter how hungry, how dark, how thirsty he was. Like now I'm outside, but we, we found that, hey, you want to go take a bath. He was like heck, yeah, I love water. But now he's progressed to we, we use the this first.

Speaker 2:We're going to do this first, then we're going to do that and we, we've worked on that and he's gotten to where he's like he's starting to understand okay, it's, okay, I can transition to this, we've got to go inside, then we'll get to go do the thing that I want to do, let's, and he's. He's come a long way in that. And transitioning tasks, um, things like I mean simple things like how to hold scissors, how to hold a pencil, just copying things, things that a normal five-year-old and I say normal and I don't mean that in the way of he's not normal.

Speaker 1:Quote, unquote normal society.

Speaker 2:Yeah, thank you, and because I don't want people coming at me going well, my kid's normal, yes, he's normal, but it's just the quote.

Speaker 1:Unquote what society says is normal. Thank you, that's what I'm.

Speaker 2:That's what I'm talking about when I say normal. I'm talking about non autistic children, what they would do compared to what an autistic child right or what David could do.

Speaker 1:Now, when they do, they tell you because I know there's a spectrum like there's a, there's a range like low to high functioning. Did they tell you when he was diagnosed where he fell?

Speaker 2:It's hard at three, because at three you're basically low functioning because you're three you're three, I mean do you get retested? You know I don't think you do. I would not be opposed to that as he got older, just because to see where he fell like not that it matters where he falls, but like sometimes it matters.

Speaker 1:like when it comes to to like how well he'll progress later or career wise in the future, or things like that, like where is he gonna, you know, fall?

Speaker 2:and it's hard to say right now, because I've seen, I have, you know, I know people in my life and you get connected. You start meeting people who are like oh, my brother, my daughter, my son, my cousin, you know, is autistic I was wondering if you were in a support group for parents I am not so much a support group.

Speaker 2:There is like a facebook group that I'm a part of and it's nobody that I've met that I would love to get. Um, you know, if anybody out there wants to reach out with like a local in huntsville group of parents of autistic children, I would love that, Um, but I'm not. But I know, you know, I've met people throughout the five years that you know have told me about their you know loved one who has autism and I'm like, well, what does that look like as an adult? And it's been everything from they've gotten married and gone to college and have kids and that, you know, leading a full life to. They still live at home and you know they function OK, but they'll never be able to live on their own or have a job, you know.

Speaker 2:So there's all different things out there. And so right now, with him being five, it's like, even though I think he's progressing wonderfully, he's using sentences, he's learning so much, and my goal and my hope is that, yes, he does, you know he is able to hold a job and I hope he gets married and has kids or whatever makes him happy. You know, I hope that's what he has, but until he's older. You know, I've seen people who were older and who were, you know, verbally wonderful, they could understand things, but when it came to actually holding a job or paying bills, they couldn't do that.

Speaker 2:But talking to them they were fine, you know. So I don't know yet, but I wouldn't be opposed to having him retested when he's older, just to see, because I want to know.

Speaker 1:Now did they tell you, like, what causes autism? Like I, I should again should have done more research. But like, is it a genetic component? Is it more environmental? Is it what we're exposed to did? Did they try to like, did they give you any information? Or, on your own research, what you found? Like what?

Speaker 2:causes autism. They did not give me any of that when I was, when we had him diagnosed. They literally just diagnose him. They send you some papers showing their diagnosis and they send you out the door. You kind of have to do your own research on that and, honestly, you will read whatever you want to read. Like if you want to read that it's caused by vaccines which it is not, by the way, and there's more proof, and my kids are vaccinated- Well, I just feel like if it was vaccines, wouldn't there be more?

Speaker 1:Yes, because like our generation, it was vaccine city.

Speaker 2:Well, and the thing is, I know there was this big, you know this doctor published this thing and he said it. But he also came back later and said I made that up.

Speaker 1:Like it wasn't a real thing. If I had to say any environmental factors, I would think it would be food does.

Speaker 2:I've done my research on that. I don't know if it causes it, but I do think it affects it.

Speaker 1:And that's my personal experience. It's got to be genetic because you're born with it.

Speaker 2:Because it's a brain thing People don't understand. It's the same thing.

Speaker 1:Well, no, that's not because I was going to say seizures, but you can develop seizures later for other things.

Speaker 2:Autism is something that affects your brain. When I tell you that they literally think about things and they process things differently than someone without autism, it's totally different. They've actually done studies, their brain scans and stuff. Their brain looks different. Their brain functions differently. They don't see things the way we see things. They don't think about things the way we think about things, and it's just amazing to me. So to me, I think it's something you're born with.

Speaker 2:I think it's genetic, I just think. To me it's no different than if you were born with a club foot. It's just the way you were formed in the womb.

Speaker 2:That's just the way your body was made and they just and that's my personal thing, I think that's how they come up, just because it's the way your brain functions, you know. And talking about that like a spectrum, people think and I think this is what I learned, this is something I didn't know and this has been enlightening was people look at autism as a linear thing. They look at a line and at one end of this line they see low-functioning, non-verbal, you know, needs help, eating, getting dressed like can't really do anything for themselves. And then at the other end of this line, like you draw a line on the paper, at the other end it is high, is high functioning. They're verbal, they can dress themselves, they can feed themselves, they can go to school like normal.

Speaker 1:They just have these little quirks about them.

Speaker 2:You know, and that's the way we look at it. And so people ask you. They're like well, is he high functioning?

Speaker 1:or is he low functioning? You do get that question a lot.

Speaker 2:All the time and they expect me to put him somewhere on that line, somewhere, and I'm like I've learned because I was the same way. It's not a line.

Speaker 1:Well, you know, I was just guilty of it.

Speaker 2:I just asked you like, did they tell you where he was on the spectrum Right? And? And the thing is, I've learned if you've met one autistic child, you've met one autistic child. Now, don't get me wrong. There's things that they kind of share, but it's no different than me and you. We're not the same exactly. But the graph and I wish you know, it's a podcast, I can't show visually, but it's more like a circle. So you, you've got this graph that's a circle and you may have. You know, this person's more proficient here and here, but less here. And this kid over here can do this and this, but less on. You know that this other kid can do this and this, but less on you know that this other kid can do and it's not.

Speaker 1:But how is that any different than if someone can sing and they're talented in singing, but they can't?

Speaker 2:read. That is exactly what I'm talking about.

Speaker 1:I've seen documentaries where like singers like are singing and they can catch a tune and they can, they can do all that. But then when someone's like hey, can you read this? They're like no, and they're like what do you mean? You can sing. Like how can you not read this? They're like I can't read.

Speaker 2:Right, that it's, it's honestly. I think that's a great analogy because, um, it's not that you know you wouldn't tell that singer. Well, that's what I'm saying. You wouldn't tell that singer, it's like, could be a very intelligent person. So it's not that someone's.

Speaker 2:And, yes, I get where the low and high functioning come. That's a great way to just Somebody's out there and they're like oh, what's your kid? I get that, but to really get to know them, it's not just about low or high functioning, there's so many different facets to it. It's like okay, for example, david's five and a half years old and we are just now potty trained to pee in the toilet. Doesn't go number two in the toilet at all, and he's five and a half years old. But on the other hand, this kid could tell you literally every fact about the planets, the dwarf planets, every name of them, facts about the things I didn't know. I mean intelligent, this kid. You can hand him a video controller and not tell him how to play the Xbox 360, and will sit there within a couple hours and expertly know how to play this game without any instruction. He is extremely smart. But on the other hand, you could say how old are you? And he's not going to answer you.

Speaker 2:I mean, or he's not going to tell you he has to go potty. I mean, so how do you say he's not smart, right? If you only looked at one aspect of it, you'd be like, oh, he's low functioning, he's, you know, he's still not potty trained and he's five and a half, or he's he can't tell you how old he is.

Speaker 1:It's almost like he does what he wants to do when he's ready to do it.

Speaker 2:It is. That's exactly what it is it's like and there's no forcing it. People are like, oh, you're babying him or you're doing, and I'm like, trust me, there's no forcing and you have to learn how to. And every child's different. Even autistic, non-autistic, every child is different. Like with David you can't yell at him Like you can't yell at him Like you can't get, he can't. And I don't want to say he doesn't get in trouble, he does. But you have to speak softly to him and you have to get on his eye level and give him deep hugs and talk to him gently, even even if he's in trouble. He can be in trouble, but you have to talk to him gently because if you don't, he shuts down. And what's the point of talking to somebody if they have shut you?

Speaker 1:out. But you know what, though that's a good point in any children? I don't have children, so I'm obviously not giving parenting advice, but I have a lot of friends with children and some parents you have that treat every single child the same. You can't when it comes to disciplinary or reward system, Right. But then you have some parents that are like no, every child is individualized. So how is it any different that you're individualizing your child's needs based on his individual?

Speaker 2:needs. Agreed, we're all different humans. Yes, I have five kids. We all respond differently. I agree with that 100%. I have five kids and there may be one kid who and don't come at me, but might need a pop on the butt.

Speaker 2:And there's another kid I could literally look at and go. That makes me sad, that makes me cry when you act like that and it would just tear them to pieces. So you have to find what works for your kid and I'm a big believer in that and I'll be honest, I'm not a gentle parent, I'm a what works for that individual kid.

Speaker 1:Yeah, now looking back, so he's almost had this diagnosis for three total years. So looking back now, knowing what you know now because you're more advanced in your knowledge, what would you say looking back? You wish you would have noticed sooner so that other parents can learn from this.

Speaker 2:So one of the bigger things that I look back and noticed is he stemmed. I didn't realize that's what he was doing. What's that? Stemming is where they self-regulate, they soothe themselves, and it could be. It could look like humming to themselves. It could be. The widest known was like hand flapping, like when they get excited. They almost look like they're trying to fly. Their little hands start flapping when they get excited and David does that. But he also hums, david. When he gets tired, he will literally run from one wall and run up and hit it with his hands and run as hard as he can to another wall until he hits it with his hands and he will do that back and forth and back and forth. I mean nonstop, and he does it around bedtime every night and he's tired and the therapist is like he needs deep stimulation, like when I talk about like giving him like really deep bear hugs or wrapping him up real tight. The therapist is like when he's doing that he needs like physical stimulation.

Speaker 1:It's almost like he can't tell you what he needs, right. But his actions are trying to show you.

Speaker 2:Yes, and we figured out that's him being tired. They said you could give him like a heavy, um, like a basket full of laundry, something heavy for him to push. What about a weighted blanket? You have to be careful with those, just when they're little, because they can suffocate just because they can be too heavy and it's hard for them to get to move. Yes, it's hard to find ones when they're that little for weight for weight.

Speaker 1:So you gotta wait until they're older.

Speaker 2:Okay, and please read the directions on the box.

Speaker 1:I didn't know, because clearly I don't have children.

Speaker 2:No, I looked into that cause that's. I think that's a wonderful idea and they do have certain things. It's not weighted blankets, but they do have a clothing for autistic children that are tight and not tight like restrictive, but just like it feels like a hug yeah, it feels like a hug, exactly. Um, and that's how I, because I did the same thing. I looked in the long quarter but I waited blankie. He needs like that, deep pressure.

Speaker 2:He needs deep pressure, um, but you have to be very careful with that okay, well, good to know.

Speaker 1:Like I didn't know, I was just like oh, a weighted blanket.

Speaker 2:That sounds, because they can get up under them and be and not move.

Speaker 1:Well, I mean, that makes sense because, like weighted blankets are for anxiety, so it would make sense, but I guess they don't make. Maybe they should make one for children that are like a half a pound.

Speaker 2:Well, agree, and they might and they could. I haven't done a lot when I first read, because I was just looking at regular weighted blankets and even for us adults they have them like if you weigh this much, you can only get it.

Speaker 1:Yes.

Speaker 2:You don't want to get them too heavy, um, but they might. Uh, there's a lot. There is a lot. There's a whole world of um, uh toys and uh clothing that's made specifically for autistic children, clothing without tags on it, fidget toys um, I'm actually looking into getting him something for christmas.

Speaker 2:It's this um, it looks like a big box and you can lay down in it and it kind of it's almost like a sling, it kind of like bundles you up like a cocoon like a cocoon, not where they can't breathe it's breathable mesh material but it kind of hugs them and they can get up under it, because david loves dark small spaces, kind of like pillow forts yes which is scary when you can't find them because they've decided to go play and david doesn't answer to his name and he's hidden somewhere. That has happened and you're just freaking out going. Okay, this kid's in this house somewhere.

Speaker 1:Where are you? So what other things did you wish you would have noticed sooner?

Speaker 2:Like I said, one was a stimming. Looking back, I didn't know this Overstimulation from noise. So when he was like one, one and a half years old, we would start the dishwasher during the day and it took us like a week. So every little bit I'd walk by and I'm like the dishwasher's off, like did I not start it? And I'd start it back.

Speaker 1:And I'd go do something.

Speaker 2:He was turning it off. He would walk in there and he wouldn't do anything other than he would push the button and turn it off at one and a half, at one. That shows you how smart he is. He knew how to turn it off. He did, and he would watch it and he'd walk away. So I did what I wasn't catching it so you know, because you know as a parent you're just like oh, I guess I'm busy.

Speaker 2:I didn't start it and I did and then I was like why did it stop? I'm thinking, is my dishwasher tore up? And after a few days of doing this, I'm noticing that every time we turn it on he just walks in and turns it off and at first I thought is this a little quirk? And then I realized it's over, like it's the noise. So we got to where we would only run the dishwasher at night because it was the noise was too much for him.

Speaker 2:I've noticed if, like we went to a baseball game back in the summer and as we're walking through the concession stand there's just tons of noise, he puts his hands over his ears and he's just like it's too much. Does he wear headphones? He does. He does, like if we're at church and the music and stuff, yes, we've got him headphones, so if it's too much noise he just puts his headphones on. It cuts out the overstimulation. He can be over-touched. Too much noise. Looking back I can see where noise was too much for him and he. You know we look around and there are times you know you're playing and you look around and he has wandered off and you're like where did he wander off?

Speaker 1:to and I'm like don't come at me.

Speaker 2:Kids wander off very quick, like within two seconds, um, and you know, and he, you know where he was. Every single time he would walk upstairs to my bedroom and get on my bed and lay down, cause it was quiet. He's in a room by himself, and so we figured that out super quick, that if it was too noisy he's gone to the bedroom.

Speaker 1:Yeah.

Speaker 2:And that was just his thing, so we let him any other subtle things that you can think of? Um, let's see the stimming, the noise I'm trying to think humming, he would. We notice he kind of hummed to himself. Oh, looking back, he doesn't do it so much anymore. But he would make this noise, this um, and I can't. I can't replicate the noise, but it was like this repetitive noise that he would make over and over, not just humming, but it was this little.

Speaker 2:I can't remember A clicking or snapping, it was some little noise he was making with his mouth and you know you think, oh, he just does that. It's this little quirk. You know, every kid has a quirk. But in doing my research I came across that noise and they're like like, yeah, the kids do this noise a lot. And I'm like david does that noise, you know is that like a soothing? It is it's every type of stem and kids are different. It is self-soothing, they regulate themselves like you know it's almost thinking about.

Speaker 1:That's almost a better way because I think humans in general, the quote-unquote normal population, we don't know how to self-soothe, we turn to alcohol, drugs, sex money, gambling, whatever you're, whatever you turn to, because you can't regulate your emotions like maybe, maybe that is the better way because they actually have figured it out. Well, I don't like the way I'm feeling, so let me soothe myself yep, and he does that.

Speaker 2:It's kind of like you were talking about the weighted blanket. When you have anxiety, you you soothe by you, you know you have these techniques, and he figured out how to do that for himself is how to self-soothe.

Speaker 1:At a very young age. Oh yeah, without you having to tell him, without anyone having to tell him, he figured that out. Yes, that's awesome.

Speaker 2:I'll tell you a funny thing. You know, in just reading stuff, because I read everything I come across, you know, and we're still learning. He's only five. I only know what I've learned with David up till now, but you know I was reading about. They did a study on adults, autistic adults, who were nonverbal as children, who, you know, learn to talk and they're fine talking and they're like can you remember that time? You know, why can you tell them? Why didn't you talk? And they found that an overwhelming number of them thought that because they could hear their thoughts in their head, that you could hear them. It was just logical for them. I can hear you speak. I can hear me speak in my head.

Speaker 2:You can hear me speak because, if I, can hear you, you can hear me, and so they didn't speak. Well, I mean, that makes sense. And for a child, I mean, how do you explain?

Speaker 1:that you know, right, I'm like that is so smart. Well, I have some facts I want to read, so if anything like it pops up, um speak about it. Brigham, I don't know.

Speaker 2:Massachusetts General Hospital. Yeah, brigham, okay, brigham, y'all know, I pronounce everything wrong, and this is from 2023.

Speaker 1:So it's just 30 facts to know about autism. So it could be updated by now, but some of these were just alarming to me, just to even read so. Autism spectrum disorder affects 1 in 36 children, which is alarming because you hear more about it now versus back in our day, but it's probably because it just wasn't talked about.

Speaker 2:I don't think they knew what it was or had to diagnose it, or they misdiagnosed them for MR and saying they were quote unquote low functioning. I agree with that a hundred percent and I think, now that we know more about it, it's not that because I know people go oh, everybody's diagnosed with autism ever, it's just everybody gets it and I'm like, no, I don't think it's more prevalent now. I just think we know more about it and are able to diagnose it better now and actually help.

Speaker 1:Right. Boys are nearly five times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with ASD, so ASD is the autism disorder. Girls are often underdiagnosed with autism and misdiagn diagnosed with ASD. So ASD is the autism disorder. Girls are often underdiagnosed with autism and misdiagnosed with other conditions and I know you want to touch on this a little bit.

Speaker 2:I do. Just because girls mask easier. And when I say mask, people are like what do you mean? I'm like they, girls can look at other people and learn how to imitate. We that, oh, we should be holding eye contact, and they do. We learn what's socially acceptable, what's the norm, and I'm not saying boys can or they don't, but girls do it so much easier that they are underdiagnosed because they're like well they're, they're functioning like they suppose they're supposed to and they're misdiagnosed with like.

Speaker 2:ADD or ADHD? Absolutely they're, they're just they and they're misdiagnosed with ADD or ADHD, absolutely. They're just. They push it off on something else and yeah, so they are well underdiagnosed. Just because masking is so much easier for girls, they pick up on intuition. Girls have this intuition. I feel, like a little bit easier than boys do.

Speaker 1:Autism spectrum disorder is one of the fastest growing developmental disorders in the United States. Asd is more common than childhood cancer, diabetes and AIDS combined.

Speaker 2:Okay, and here's my thing Again. Like I said before, I don't think that it's more prevalent now than it ever was. I just think that we recognize it now.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and this fact was just saying, if you think about all these disorders, that are common think about it, as in the fact of autism is actually more prevalent than all three of those combined.

Speaker 2:So think about this what if? What if it's not? I mean and yes, I agree with that, it's probably it's more prevalent than all that combined. But what if autism isn't so much a disability, but it's just the way the other half is Okay, think about it this way. You know how you have people with there's blonde hair and dark hair. And we don't think anything about it. You have blonde hair.

Speaker 1:I have dark hair. You're left-handed, I'm right-handed.

Speaker 2:Period, that's just it. Nobody thinks anything about it. What if It'll get? This person thinks this way and this person thinks this? We just have a name for it. We just call it autism. We have a name for it. But what if it's always been that way? And that's why we think oh my God, there's so many people with autism and it's like it's just how somebody's brain works. It's like why is that any different than you know any like? I'm right handed, you're left handed.

Speaker 2:We don't go. Oh my God, that person is left handed. They've got a disability.

Speaker 1:Well, because left handed people are more artistic, like that's been proven.

Speaker 2:Right handed people have more logical or whatever it is, but we don't say they have a disability Right.

Speaker 1:And, but that's been proven. That's how they think, exactly.

Speaker 2:Right.

Speaker 1:They have a different way of thinking, just like so. So what autistic children have a different way of processing their information than we do? Right, all right? Asd affects all nationalities, all creeds, all religions, all races and both sexes.

Speaker 2:It doesn't differentiate or affect only one group agreed because, again, it's not anything that we're doing, it's just how we're born um, self-advocacy is an important skill.

Speaker 1:That is an important skill. That is especially important for autistic individuals. In order to be a great self-advocate, people first must know what their strengths are, as well as what accommodates and serves them the best. With that knowledge, they can be their own best advocate, with family, school and community Agreed.

Speaker 2:But I think as parents, before they get to that point, like with David agreed but I think as parents. Before they get to that point, like with David, we have to be their advocate. Correct? Because, um, you know, if David is non-verbal, he's not going to talk or he's not paying attention.

Speaker 2:If you didn't know that, or if you didn't understand autism, you're thinking well, he's being rude, he's, he's not speaking to me or he's not looking at me or you know, and it's like no, you just don't understand where he's coming from and I'm going to be the first to be like you need to back off.

Speaker 1:And touching on schools a little bit, I know you wanted to kind of talk about schools and autism a little bit.

Speaker 2:Yeah, so some sad things. You know, david is five and he's coming up on. He should have started kindergarten this year. Most kids start at five.

Speaker 2:So I went to the school armed with the knowledge that you know we've he's been diagnosed with autism, and so I talked to them. I'm like, hey, what resources do you offer here? And of course they're like we offer resources, we have aides that come into class, we have smaller class sizes, and I'm like that's amazing, so let's do that. And they're like well, it's not that easy. Amazing, so let's do that. And they're like, well, it's not that easy. We have people that will come in and assess and diagnose your son. I'm like that's not necessary. I've already had him diagnosed.

Speaker 2:He's been seen, you know, by doctors at the Raleigh Center, which that's what they do pediatric neurologists like he has this diagnosis. And they're like, no, no, we, as the school system, we have to diagnose him, we have to assess him, and we'll have our own person come in and the teachers. And on top of that I'm like, well, okay, if that's what you have to do. But then they go further and they're like we're going to he has to start out in a regular classroom. And I'm like why? Because I know from previous experience David doesn't do well in large groups. He just doesn't, and they're like. Well, we have to prove that his disability impedes his learning. He has to fail for us to give him the resources he needs and as a parent, that's hard to swallow.

Speaker 1:Yeah.

Speaker 2:How do you send your child to school knowing that he is going to get overstimulated and they're not going to do anything about it at first? No, don't get me wrong. I'm not saying the school system's bad. I know people who have their kid in a regular school system and it's wonderful. But to get to where he needs to be, he has to fail, he has to be overstimulated. And I know when David gets overstimulated he might act out, he might scream, he's not going to listen and it's going to look like he is a defiant child. It's going to look like he is not paying attention in class and he's acting up and I'm like but that's not what he's doing and that's not who he is.

Speaker 2:He's just overstimulated and you don't know how to deal with him, so he has to go through all that he has to go through. Could you imagine if I stuck you in a place that you were extremely uncomfortable in and put you in all your worst anxieties, and I stuck you in that room and said deal with this.

Speaker 1:And only if you can't deal with it we'll help you, and maybe you need to do something like some advocacy there and see if you can get that changed?

Speaker 2:I would love that. I'm all new to this, so if there's people out there that says, hey, this is how you get started, and I'm looking into it, but I'm so new because he was just supposed to start this year. I'm so new to it. I just don't understand why it's got to be that way and, like I said, I'm new. I know there's people out there that are probably going to be like well, all you've got to do is this, or you need to do it this way.

Speaker 1:And I'm open to all of that. All right, some more um which you touched on. This, um, autism spectrum disorder is a developmental disability that often presents with challenges for the age of three and last throughout their lifetime. Right Um early identification, treatment and support matters. Many important outcomes for children's lives are significantly improved with early diagnosis and treatment which you touched on.

Speaker 1:Early behavior-based interventions have positive effects on some children and they did put some children with autism spectrum disorder and less noteworthy effects on other children, which is what you were talking about with the asd. Not asd, but the um. What was the behavioral? The aba? Therapy I believe that's what they're talking on, right um.

Speaker 1:Early service needs to be based on individual children's needs and learning styles services for adults with asd must be carefully individualized, meaning like people who were diagnosed later in life. Right? There is currently no medical detection, blood test or cure for autism spectrum disorder. Parents do not and cannot cause autism spectrum disorder, right? I love that they put that in there, because I know a lot of parents blame themselves.

Speaker 2:You do, cause people are like, oh well, you took this, there's a thing out going. If you took Tylenol you could have caused it.

Speaker 1:It says although the multiple causes of ASD are not known, it is known that parental behavior before, during and after pregnancy does not cause ASD, so I love that they put that in there. Because I know, parents in general just blame themselves for anything that their children are going through.

Speaker 2:Absolutely, because you're thinking well, did I not take the right vitamins during pregnancy? There's a whole Tylenol lawsuit out going. Well, if you took Tylenol during your pregnancy and your child's autistic, you could have caused it. You're thinking, oh my gosh, did I do this? And no, you did not do this, this is just. Your child was born that way, End all be all.

Speaker 2:And you talked about um support, having a good support system, and that is so important because if you don't, you know when he, when David, was first diagnosed, his dad had a little bit of trouble accepting it. And he does now, don't get me wrong. He does and he's fully supportive. But when he was very first diagnosed he just didn't want to believe it. Not that he wasn't trying to be supportive, it was just.

Speaker 1:I mean, it's a hard thing that you know that your child's about to go through something hard in life, Right.

Speaker 2:And you will. It shatters all this. You have this picture of how your child's life is going to be. You know all this normal stuff and it's just shattered and it just it's hard to swallow that, to think that that's not what it's going to be anymore. But my mom told me she said well, now she goes. Look at the bright side, she goes. You can let go of all these expectations you had for David and start focusing on the things that he can do and not focus on the things that he's not doing. And I was like you're absolutely right.

Speaker 1:Correct. Um. Many individuals with autism spectrum disorder have difficulties with communication. For some people this can look like significant challenges with spoken language and for others it can look like challenges with social communication, which you touched on. Um, asd is not a disorder that gets worse with age right. Individuals with asd can learn and build new skills with the right support and are most likely to improve with with specialized, individualized services and opportunities for supported inclusion agreed being non-verbal at age four does not mean that a child with autism will never speak.

Speaker 1:Agreed, you know that. Firsthand research shows that most will learn to use words and nearly half will learn to speak fluently yep, absolutely, it just takes um.

Speaker 1:You know, like you said, the right support which we found, which I love that we talked about it first and then going through all these facts, because you kind of touched on most of these already and it just shows, like david, like he is autistic, because, like, look at everything we're talking about, right, and what you've been through, um. It further says children and adults with autism spectrum disorder are off, often care deeply but struggle to spontaneously develop empathy and socially connect to typical behavior. Individuals with asd often want to interact socially but lack the ability to spontaneously develop those social skills. Right, um, supporting an individual with autism spectrum this, this one is what got me okay. Supporting an individual with autism spectrum disorder cost a family sixty thousand dollars a year on average. The cost of lifelong care can be reduced by two-thirds with early diagnosis and intervention, according. According to a recent study, the lifetime cost of autism averages between 1.4 million to $2.4 million.

Speaker 1:I can absolutely see that I mean it makes sense, with all the therapies and things that you're having to put your child in. Right, I mean that's just I mean, think about like. I mean most of us are middle class and like especially with today's economy, that is just not feasible.

Speaker 2:Well, it's daunting to think that your child needs a therapy and or they need something and you can't afford it. And you're thinking am I failing my child because I can't afford 1000s of dollars of therapy every single week? And honestly, we got to that point. David was in therapy every week and he luckily for us, he progressed so well that you know one was he was progressing so well. We thought, hey, we can cut back. But part of our decision was financial you know, it's like it was thousands of dollars.

Speaker 2:I'm like it's it was getting tough, especially today, and so I sat down with this therapist and I explained you know our situation and they were super supportive and understanding and we get that. We agree that he is progressing, so let's cut back. Here are things they would email me things and give me papers and go. Here are things that we want you to work on at home and we would talk about things together Like what do you want him to work on?

Speaker 2:Here are things that he needs to um, the skills he needs to have to start kindergarten. Here are things that you want him to work on. Here's how you do that. And then we'll check back in a month or two months. And so I get to go home and they would send me all these resources, videos and books and stuff real resources, videos and books and stuff real things I could use, real tools and so we get to do that at home and then we check back in now if there's stuff that he's doing great on we I make notes of that. If there's things I'm like he's not doing great on this one thing, you told me how could we do better? And then that's what we go over and we add new skills. So you know I had great therapists to work with that gave us tools to go home and work with.

Speaker 1:Co-occurring medical conditions in autism spectrum disorder are common. It may include allergies, asthma, epilepsy, digestive disorders, feeding disorders, sleep disorders, sensory integration dysfunction, cognitive impairments and other medical disorders. Yes, children and teens with autism often have lower bone density than their peers, which that was a random fact.

Speaker 2:I did not know that and that's you know.

Speaker 1:Up to a third of people with autism spectrum disorder also develop seizures. The rate of seizures in people with ASD is 10 times higher than in general population, and I would assume it's just because their brain activity is just overstimulated. Yeah, absolutely. About 10% of people with autism spectrum disorder also have another genetic, neurological or metabolic disorder. Each person with autism spectrum disorder is a unique individual. People with ASD differ as much from one another as do all people.

Speaker 2:Yes.

Speaker 1:Children and adults with ASD may speak or interact with others. They may have good eye contact. They may be verbal or nonverbal. They may have good eye contact. They may be verbal or nonverbal. They may be very bright or average intelligence or have cognitive defects, just like everyone else.

Speaker 2:Right. So that's what I'm saying is, they're no different than anyone else. They literally just process information differently than we do.

Speaker 1:And then it says hyperlexia, the ability to read above one's age or grade level in school, commonly accompanies autism. Which you said with David and the planets, yes, you could show him like.

Speaker 2:You could write down that, even at two, but he wasn't talking to you having a conversation. But you could write down the name of any planet without any other context but just the word, and he'd tell you what it was.

Speaker 1:And that's like that show I was telling you about, which I should have looked up the name of it.

Speaker 2:He obsessed about penguins and he could tell you any fact about penguins every fact about penguins.

Speaker 1:All right, moving on to the next one, individuals with autism spectrum disorder may be very creative and find a passion and talent for music, theater, art, dance and singing quiet or sorry, singing quite easily. Children with autism are 160 times more likely to drown than typical children. Therefore, it is very important to teach them to swim and to keep an eye on them around water.

Speaker 2:I agree. I will say this David has no fear. No fear. Like you know, some kids get up high and they think, oh, I don't want to jump because I am going to fall on the hard ground. David could be a million feet up, he doesn't care, he's going to jump, he I mean he will jump into off of. Luckily, like we took him to the pool and luckily his dad like before I even got his little uh life vest on his dad was standing in the pool. It was like waist deep on him and there was a float sitting right beside him. David takes off running before anybody could catch him, jumps in the pool, but luckily he lands on the float and his dad was literally standing right beside him. I mean, we were both right there, but still he had no fear, he couldn't swim, he didn't care.

Speaker 2:He's jumping right on in the pool, he jumps off of things. And he also has another weird thing and it may be on there he has a high tolerance for pain, things that other kids would be crying over her he doesn't. So if he's crying, he's hurting like he has a super high tolerance for pain.

Speaker 1:Researchers and clinicians hypothesize that symptoms of autism spectrum disorder in males and females may differ, leading many females to be diagnosed later than males. Females with autism spectrum disorder in males and females may differ, leading many females to be diagnosed later than males. Females with autism spectrum disorder are often an understudied group in research which they kind of touched on at the beginning. So I'm not sure why they put that later.

Speaker 1:Gender differences and symptoms have been found with the areas of social understanding, social communication and social imagination. But let's be honest, that's with everybody, females and males, when it comes to like emotional and logical sides of the brain. That's normal with everybody. Um, about 50,000 individuals with autism spectrum disorder will exit high school each year in the United States Many services required by law and abruptly after high school, leaving young adults under supported Yep, and that's sad to me. It is sad. It is sad um. 35 of adults with autism spectrum disorder have not had a job or received postgraduate education after leaving high school, probably because they don't have the support because it just abruptly stops, like it should be transitioned.

Speaker 1:It almost should be like you know how you go to high school to college, like to transition out of it to learn to do things on your own. They should have the same transitioning period Because, like you said, they have a difficult time transitioning. Employers are recognizing that creating a neurodiverse workforce is fundamental for success. Companies that recruit, retain and nurture neurodivergent employees. I like that. That they call them neurodivergent, yes, instead of autistic.

Speaker 1:We also like the term neuro-spicy neurodivergent yes, instead of autistic we also like the term neuro spicy and nurture neurodivergent. Employees gain a competitive advantage in the areas of productivity, innovation, culture and talent retention, to name a few. There is no federal requirement for providing supportive services to people with autism in adulthood. This leaves many families navigating these types of services on their own.

Speaker 2:Yes, and that I'm hoping that changes and I would love to be a big advocate for that change because, um, you wouldn't tell somebody in a wheelchair Tracy, start a movement. You wouldn't tell somebody in a wheelchair going. Well, you know it sucks to be. You figure it out, you know and you don't, and it's like you can't go back and forth between saying, well, you've got a disability and you know well okay.

Speaker 1:But we're not going to recognize that. And when I was saying figuring it out, I was piggybacking off of you, Like no one says to someone in a wheelchair to figure it out.

Speaker 2:No, I know exactly what you mean. You can't get up those stairs. Oh well, figure it out. Sucks to be you. No one says that.

Speaker 1:No, because it's a federal law that you have to have handicap access.

Speaker 2:And that's okay. That makes a great point. If you don't see something physically wrong with somebody, you assume that everything is just okay.

Speaker 1:Well, let's take it a step further. Depression and anxiety. Thank you, you're not physically going to see something wrong with them until it's too late, right?

Speaker 2:So any kind of emotional, neurological, like having to do with a brain.

Speaker 1:Okay, so me like with my hypothyroidism there's some days where I feel so bad, I feel so low, yep Same, and my mood kind of you know it changes because it depends on my thyroid levels. Right, and there are some days where I'm like super happy and energetic and want to talk to people all day. And there are some days where I'm like, can you just not? Yes, but people don't understand that because it's not physically present. They're like, well, what's wrong with you today?

Speaker 2:Right, it's unseen, and anything that's not physical, if you're not on you know, like if you have a migraine.

Speaker 1:Yep.

Speaker 2:And it's like the most debilitating pain I've ever had in my entire life. People are like I mean, can't you just take a Tylenol? And I'm like you cannot. No, you cannot. And so hopefully you know I'm a huge advocate. My whole family is. We're huge, huge advocates for, you know, mental health awareness whether that be anxiety, depression, adhd, um autism, I mean. There's just there's all these mental health things, that is, they go unrecognized because it's there's such a stigma.

Speaker 1:Right.

Speaker 2:You're just crazy. If you're not mental going on, they think mental crazy and I'm like no, your brain is an organ in your body, just like your heart and you can't control it. No, it's like if you had high blood pressure and you take medication, nobody goes. Well, you're just crazy.

Speaker 1:Right. Why are you taking blood pressure medication?

Speaker 2:Right Agreed. You can't control that. You can't think oh well, my heart needs to quit doing that, let me fix that. Just like you can't go, oh well, my brain needs to stop firing that way. I need to. You can't.

Speaker 1:Agreed. So so the last one we have. Many people with autism spectrum disorder are successfully living and working and contributing to the well-being of others in their local communities. This is most likely to happen when appropriate services are delivered during child's educational years Right With lots of support from family, from friends. Communities, churches.

Speaker 2:Yes, recognizing and supporting those around you. You know it keeps coming back to my mind. One of the funniest things. It's not funny, it actually upsets me, but it makes it. I have to laugh.